What's the Use of Fiction?

/Every so often I run into a pocket of people who have very decided opinions about the value of fiction. Negative opinions.

The reason is usually some variant of this:

"I don't want to read pretend, made-up stuff. I prefer the real world. Things that are true. I don't have the time or need for this other stuff."

The first time I heard this, I was startled. It never occurred to me that people would not want to read fiction. My reading diet has always included an ample supply of both fiction and non.

Nonfiction does some things better than fiction can. And fiction does some things better than nonfiction can. They both move the mind and the heart, but use different ways to do so.

And as to the claim that fiction just isn't true, well, let's take a look at the whole reading world.

Nonfiction is not always true. It can be either true or false, usually a mixture of both. Fiction can also be either false or true.

There's a book on my writing shelf called The Lie That Tells a Truth. It's a guide to writing fiction by John Dufresne. It's got some good points in it, helpful instruction, but I find myself objecting to the title.

Fiction is not a lie. It would be a lie if it told you that the events of the story it relates really happened, and you found out later that they didn't.

Fiction never claims things really happened. You know from the outset that it is a story, complete with setting, characters, motivation, plot events and more. And usually by the end of the first chapter you know what the story is promising to do.

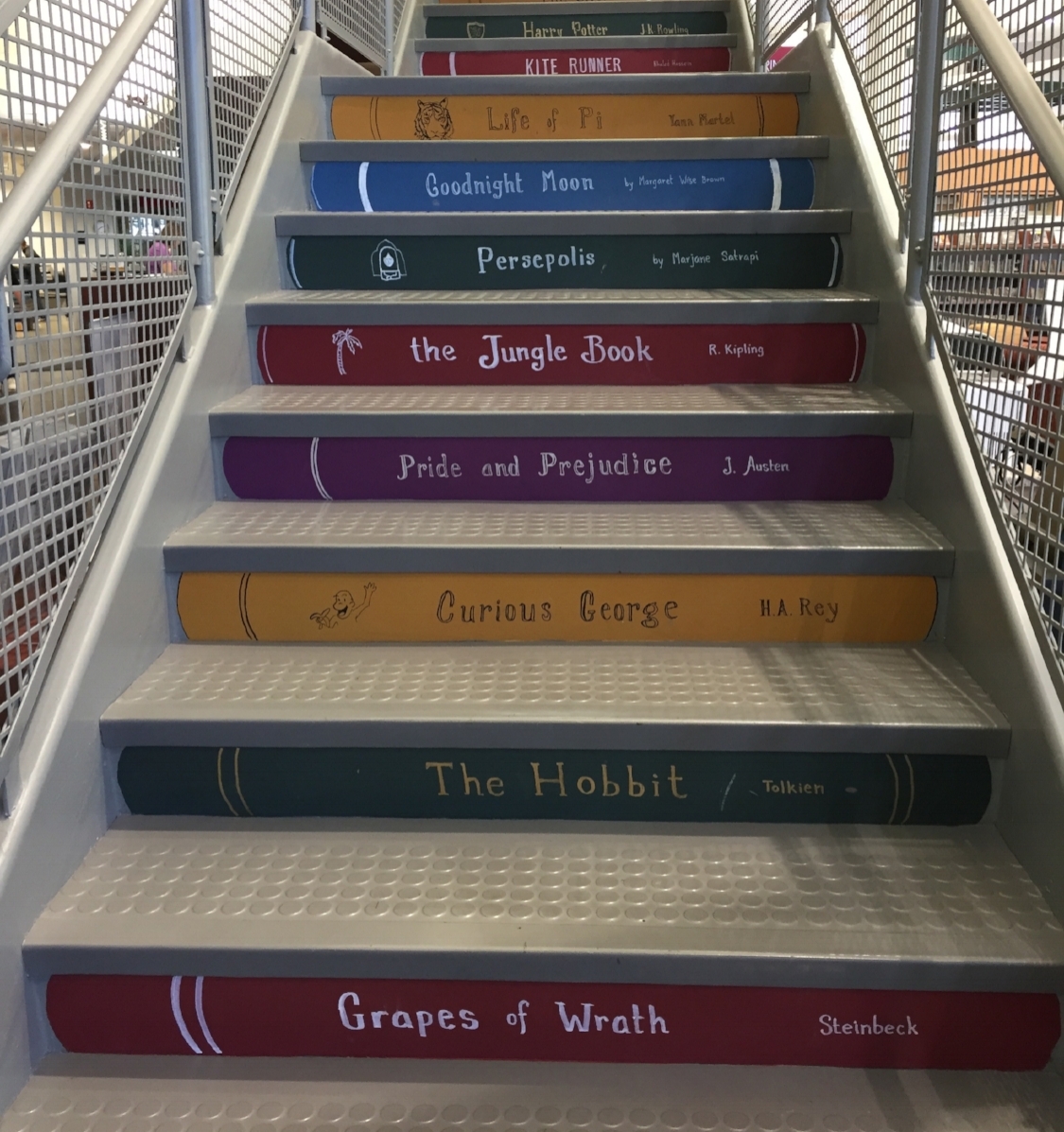

Jane Austen never tries to convince you that Elizabeth Bennet really lived. But she does explore the birth and death of human prejudices and uses Elizabeth and Darcy to do so.

Tolkien does not urge you to hunt for hobbits and elves in the park down the street from your house. Yet he pulls you to experience and wonder at a complex world filled with good and evil, danger and love, sacrifice and heroism.

Good fiction, true fiction, enlarges the reach and understanding of the human heart. When a heart is engaged in a story, the story has the power to change the heart.

Here's one of my favorite examples from history.

A troubled man walked down a palace corridor toward the audience chamber of the king. He might have been fearful. It's hard to tell several thousand years distant. But it's a good bet he was cautious. Because he was in a dangerous place.

He had the unenviable task of correcting a ruler gone renegade. A ruler who certainly did not want to be corrected. A ruler who definitely had the power to destroy anyone who challenged him.

What would this man say? How would he approach the guilty king?

With statistics? With opinion polls? With logical arguments? By appealing to the king's best interests?

Our man in the corridor chose none of these. When he was ushered into the king's presence, he opened his mouth and began like this.

"There were two men in a certain town, one rich and the other poor..."

It was a story. Fiction. But it engaged the hearer's heart and emotion. By the time the story ended, the king was furious at the injustice it related. Then, the fury turned to repentance.

Before the king's heart could be changed and reasoned with, it had to find itself in a story.

The king was David. The country was Israel. The man in the corridor was the prophet Nathan, whom God had sent to David. With a story.

All sorts of things can happen when a story shows up.